A fictional piece

Eleanor had always lived a life of faith. Raised in a devout Christian family in England, the church was at the center of her world—Sundays filled with hymns, prayers, and sermons that affirmed her belief in God. As she grew older, her faith remained, but so did her curiosity about the world outside her religious bubble. Her yearning for something more brought her to India, a land known for its spiritual depth, but also a land whose philosophies she had barely scratched the surface of.

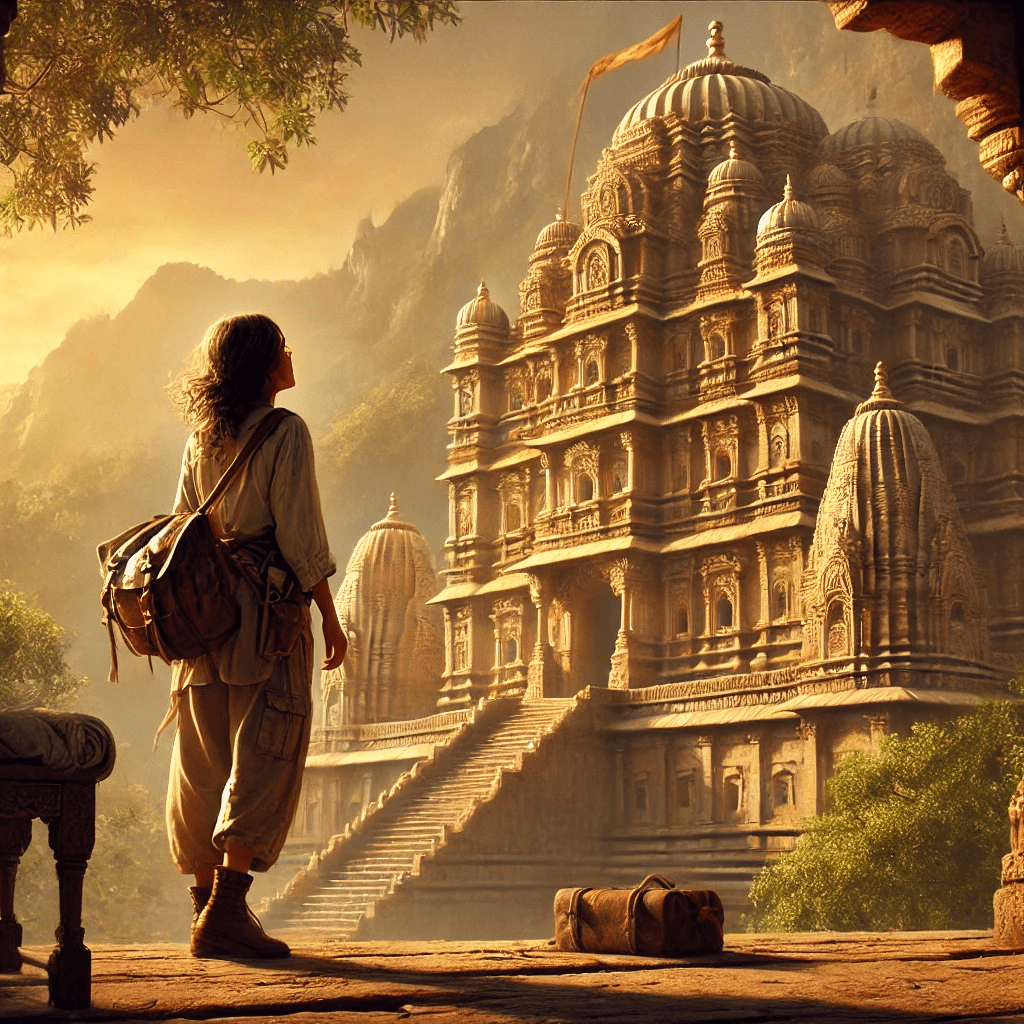

On a whim, Eleanor decided to take a solo trip to India, eager to explore its rich spiritual traditions. She imagined she’d find peace in the temples, seek wisdom in the scriptures, and connect with a deeper sense of God. But what she found was something entirely unexpected—a challenge to the very idea of God itself.

Her first stop was a Jain temple, a marvel of intricate carvings and quiet reverence. She was drawn to the temple’s atmosphere of serenity and discipline. While collecting some Jain literature, she stumbled upon a peculiar fact: Jainism, one of the oldest religions in India, does not believe in God. There were no creators or divine beings guiding the universe in Jain philosophy. The focus was instead on the soul, karma, and non-violence. Eleanor was puzzled. How could an entire religion exist without a god? The idea seemed so foreign, so radical, yet deeply intriguing.

Leaving the temple, Eleanor found herself reflecting on this revelation. She had come seeking spirituality, but her journey was now taking her in a direction she hadn’t anticipated. She traveled further, meeting a yogi in Rishikesh, hoping to learn more about yoga and perhaps find the God she was searching for. The yogi, a calm and wise figure, taught her the physical and mental practices of yoga, emphasising discipline and self-realisation. After days of learning, Eleanor asked him about his belief in God.

To her shock, the yogi smiled and replied, “I do not believe in God.”

This struck Eleanor even harder than the Jain revelation. How could someone so spiritual, so connected to the divine energy of life, not believe in God? She had thought yoga was a pathway to God, but here it was being taught as a discipline to transcend the very need for a divine entity. It was another crack in her understanding of spirituality.

Curiosity consumed her. Eleanor had heard of Buddhism and its philosophical importance in India, so she decided to explore it further. She made her way to Bodh Gaya, the site of Buddha’s enlightenment, then to Ladakh and Tibet, places where Buddhism flourished. As she delved into Buddhist teachings, another revelation shook her to the core: the Buddha didn’t believe in a god either, nor in an eternal soul or spirit.

Buddhism taught that life was a cycle of suffering caused by attachment and desire, and the path to enlightenment was through understanding the nature of reality—not through prayer or worship. The absence of a creator, the denial of a permanent soul—this was a philosophy that shattered every religious assumption Eleanor had ever held.

“How can a religion exist without God or even the soul?” she wondered. Everything she had known about religion seemed upended by these ancient traditions. India was not just a land of gods—it was also a land of radical philosophies that questioned the very existence of divine beings, spirits, or an afterlife.

Seeking answers, Eleanor returned to Delhi. She visited libraries and universities—Jawaharlal Nehru University, Jamia Millia Islamia, and Delhi University—pouring through texts and philosophical treatises. The more she read, the more she discovered that India had been home to entire schools of atheistic thought. She learned that out of the nine classical schools of Indian philosophy, eight of them—including Jainism, Buddhism, and Sankhya—either questioned or outright denied the existence of a personal god.

But the most shocking revelation came when a history and philosophy lecturer introduced her to the ancient Charvaka school, also known as Lokayata. Charvaka was a materialist philosophy that rejected the existence of gods, karma, an afterlife, and even the soul. The Charvakas believed that only what could be perceived by the senses was real. The idea that there was no divine reward or punishment, no life after death, and no soul to carry on beyond this life—it was unlike anything Eleanor had ever encountered.

Yet as she eagerly searched for Charvaka texts, Eleanor was met with disappointment. The original works of the Charvakas were nowhere to be found. “Most of what we know about Charvaka comes from their critics,” the lecturer explained, “Those who opposed their ideas wrote about them, often to discredit them. The original texts are lost to history.”

This deeply unsettled Eleanor. How could such a bold, radical philosophy have been erased from the annals of history? She felt a pang of injustice. Here was a land that had given birth to some of the most profound ideas humanity had ever seen, and yet the voice of one of its most daring schools of thought had been silenced. “What a shame,” she thought. “To lose such radical ideas to time and prejudice.”

She reflected on this—how society, even one as philosophically rich as India’s, could suppress ideas that threatened the status quo. The thought haunted her as she returned to her hotel each evening. The more she learned, the more she realized how history was written by those in power, and how easy it was for entire schools of thought to vanish, leaving only traces in the writings of their opponents.

By the time Eleanor returned to England, her life had changed in ways she could never have imagined. She had embarked on her journey seeking God, but instead, she found herself immersed in a world of atheism, skepticism, and materialism. She had been forced to confront the limits of her own faith, and in doing so, she had grown. She no longer needed the certainty of a personal god to find meaning in life. Instead, she found beauty in the questions, in the exploration of ideas, and in the understanding that life could be profound without the need for divine intervention.

Eleanor’s journey had led her through India’s ancient wisdom, from the non-theistic spirituality of Jainism and Buddhism to the radical materialism of Charvaka. The country she had once seen as the land of gods was now, in her mind, the land of bold thinkers—people unafraid to question, to explore, to challenge the very nature of existence. India, she realized, was not just a spiritual haven—it was a land where atheism and philosophy flourished side by side, where the quest for truth mattered more than the quest for divinity.

And Eleanor, too, had found her truth—not in the temples, not in the scriptures, but in the realization that the world was full of possibilities she had never dreamed of.

Leave a comment