By Maq Masi

India, a cradle of profound philosophical traditions, has fostered a diverse array of systems that explore the nature of existence, consciousness, and reality through rigorous intellectual inquiry rather than theistic belief. Since ancient times, Indian philosophy has been predominantly atheistic, with eight of its nine major schools (darśanas) rejecting a creator God in favour of rational, empirical, or meditative approaches (Radhakrishnan, 1923). Rooted in the Vedic and post-Vedic periods (circa 1500 BCE onward), these traditions prioritise questions like: What is the self? How did life come into being? What is the nature of reality? This article delves into the atheistic underpinnings of Indian philosophy, examining the nine darśanas, their classifications, and key concepts such as dharma, ātman, kāma, and karma, while highlighting their divergence from Western theistic frameworks.

The Context of Indian Philosophy

Indian philosophy emerged from a quest to address fundamental questions through rational inquiry, direct experience, and logical analysis, often independent of divine revelation (Dasgupta, 1922). The nine major schools, known as darśanas (perspectives or visions), are traditionally divided into āstika (orthodox) and nāstika (heterodox) systems based on their acceptance or rejection of the Vedas as an authoritative reference. However, this classification does not align with Western notions of theism (belief in a creator God) or atheism (rejection of a creator God).

Theism and Atheism in Indian Philosophy

In the Indian context, āstika schools accept the Vedas as a reference point, while nāstika schools reject their authority (Radhakrishnan, 1923). Crucially, neither category inherently implies belief in a creator God. The Western concept of theism, centred on a monotheistic creator, differs from Indian traditions, where divinity is often impersonal, pantheistic, or absent (Matilal, 2002). The term “religion,” derived from the Latin religio (reverence or obligation, emerging around the 8th century CE), has no direct equivalent in ancient India (Flood, 1996). Instead, Indian traditions used dharma, a term with roots in pre-BCE texts, encompassing a broader scope than religion.

Etymology and Meaning of Dharma

The word dharma derives from the Sanskrit root dhṛ (to hold, sustain, or uphold). In the Rigveda (circa 1500–1200 BCE), dharma refers to the cosmic order or natural law sustaining the universe (Rigveda 10.129, trans. Jamison & Brereton, 2014). Over time, it evolved to include ethical duties, social obligations, and individual righteousness, depending on context (Olivelle, 1996). Unlike “religion,” which implies organised worship or belief in a deity, dharma encompasses moral, social, and cosmic order without necessitating a creator God. In Buddhism and Jainism, dharma refers to teachings or the path to liberation, not a divine mandate (Gethin, 1998).

Classification of Indian Philosophical Systems

Indian philosophy is categorised into nine darśanas, grouped by their approach to understanding reality through means of knowledge (pramāṇas): perception (pratyakṣa), inference (anumāna), and testimony (śabda), or combinations thereof (Dasgupta, 1922). These systems address the origins of life and existence differently:

- Sāṃkhya: An atheistic, dualistic system positing two eternal realities—puruṣa (consciousness) and prakṛti (matter). It explains the universe’s evolution through their interaction, without a creator God, relying on inference and analysis (Sāṃkhya Kārikā, trans. Larson, 1969).

- Yoga: Aligned with Sāṃkhya, Yoga emphasises meditation and discipline for liberation. While some interpretations acknowledge Īśvara as a meditative aid, it is not a creator God, making Yoga largely atheistic (Yoga Sūtras, trans. Bryant, 2009).

- Nyāya: A logical system focusing on epistemology and reasoning. Early Nyāya was atheistic, relying on perception and inference, though later texts introduce Īśvara as an efficient cause (Nyāya Sūtras, trans. Datta, 1939).

- Vaiśeṣika: Known for its atomistic theory, positing indivisible atoms (paramāṇu) as the universe’s building blocks. Early Vaiśeṣika was atheistic, with later theistic elements (Vaiśeṣika Sūtras, trans. Sinha, 1911).

- Mīmāṃsā: A Vedic ritualistic school prioritising the Vedas’ authority and ritual efficacy. It is atheistic, rejecting a creator God and focusing on dharma as duty (Pūrva Mīmāṃsā Sūtras, trans. Jha, 1942).

- Vedānta: Based on the Upaniṣads and Brahmasūtras, Vedānta includes Advaita (non-dualistic, with Brahman as impersonal) and Dvaita (dualistic, positing a personal God). Even in theistic Vedānta, the creator is an aspect of Brahman, not a distinct entity (Brahmasūtras, trans. Thibaut, 1904).

- Cārvāka: A nāstika materialist school rejecting the Vedas, afterlife, and supernatural entities, relying solely on direct perception (Sarvadarśanasaṅgraha, Mādhava, trans. Cowell & Gough, 1882).

- Jainism: A nāstika tradition rejecting Vedic authority and a creator God, emphasising self-discipline, non-violence, and eternal souls (jīva) (Jaini, 1979).

- Buddhism: A nāstika system denying a creator God and Vedic authority, focusing on the Four Noble Truths and nirvāṇa (Gethin, 1998).

Of the nine darśanas, eight are atheistic in the Western sense, as they do not posit a creator God. Only certain Vedānta sub-schools (e.g., Dvaita and Viśiṣṭādvaita) align with theism, but their concept of a creator remains distinct from Western monotheism (Sharma, 1960).

The Concept of Ātman and Its Rejection

The concept of ātman, often translated as “self” or “soul,” is central to most Indian philosophies but differs from the Western soul, which implies a created, individual entity subject to divine judgment (Radhakrishnan, 1923). In Indian thought, ātman is the eternal, conscious essence, either singular and identical with Brahman (Advaita Vedānta; Chāndogya Upaniṣad 6.8–16, trans. Olivelle, 1996) or plural and distinct from matter (puruṣa in Sāṃkhya and Yoga; Sāṃkhya Kārikā, trans. Larson, 1969). Nyāya, Vaiśeṣika, Mīmāṃsā, and Jainism (where it is called jīva) also accept ātman as fundamental.

Two darśanas reject ātman:

- Buddhism propounds anātman (no-self), asserting that there is no permanent self, only transient aggregates (skandhas: form, sensation, perception, mental formations, consciousness). This underpins its view of life as interdependent and impermanent (Dhammapada, trans. Gethin, 1998).

- Cārvāka denies ātman as a non-physical entity, arguing that consciousness arises from the body and ceases at death (Sarvadarśanasaṅgraha, Mādhava, trans. Cowell & Gough, 1882).

The ātman debate highlights the diversity of Indian philosophy, with most schools positing an eternal self, while Buddhism and Cārvāka offer radical alternatives.

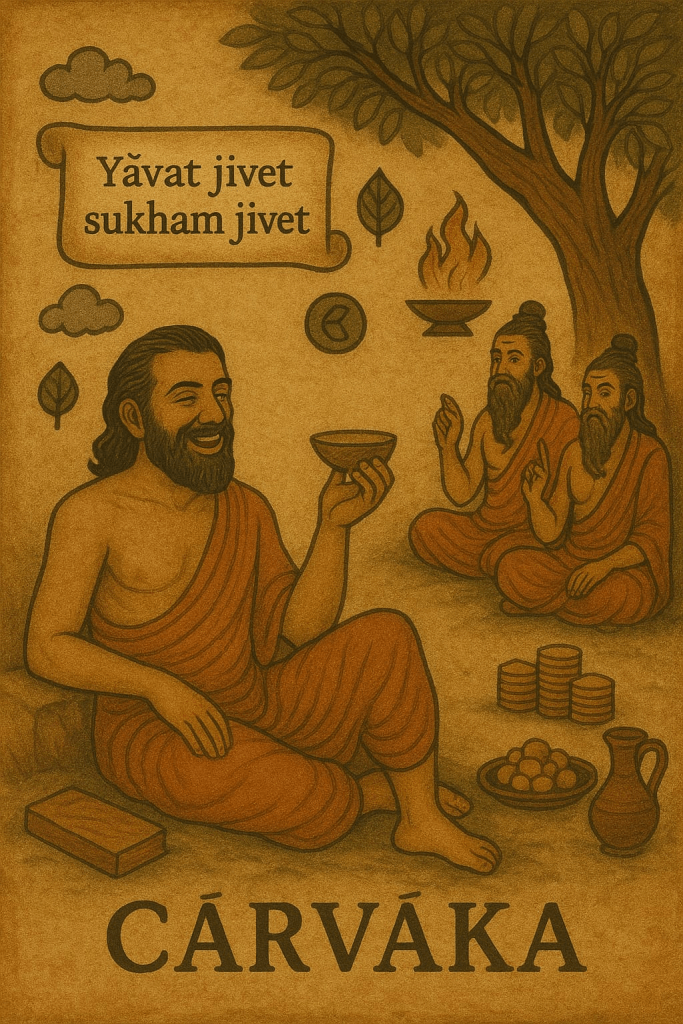

The Cārvāka School: Materialism and Hedonism

The Cārvāka (or Lokāyata) school, possibly named after its founder or from caru-vāk (“sweet speech”), is the most explicitly materialist and atheistic darśana. It rejects the Vedas, ātman, karma, rebirth, and supernatural entities, accepting only direct perception (pratyakṣa) as valid knowledge (Sarvadarśanasaṅgraha, Mādhava, trans. Cowell & Gough, 1882). Cārvāka posits that the universe comprises four elements—earth, water, fire, and air—with consciousness emerging as a byproduct, akin to intoxication from fermented ingredients (Chattopadhyaya, 1959).

Cārvāka’s hedonism advocates rational pleasure (kāma) as the highest good, given life’s finitude and the absence of an afterlife. As Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya argues, this ethic was a secular critique of Vedic asceticism, grounded in empirical reality (Lokāyata, pp. 20–25). The school’s slogan, “As long as you live, live happily; drink ghee, incur debt,” reflects this practical approach (Sarvadarśanasaṅgraha). Cārvāka challenged Vedic orthodoxy, particularly Brahminical authority, viewing rituals as exploitative (Matilal, 2002). Its rejection of inference limited its explanatory scope, drawing criticism from Nyāya and Vedānta, and few original texts survive due to its marginalisation (Chattopadhyaya, 1959).

Kāma and Sexual Depiction Sculptures in Indian Culture

Kāma, meaning pleasure or desire, is one of the four puruṣārthas (goals of human life) alongside dharma, artha, and mokṣa (Doniger & Kakar, 2002). While not a darśana, the concept of kāma is addressed in Indian philosophy, with varying emphasis. The Kama Sutra (circa 3rd–4th century CE), attributed to Vātsyāyana, is a treatise on kāma, covering sexuality, relationships, and social conduct, advocating regulated pleasure within the bounds of dharma and artha (Doniger & Kakar, 2002). Unlike Cārvāka’s hedonism, which prioritises kāma as the sole good, most darśanas (e.g., Sāṃkhya, Yoga, Jainism, Buddhism) subordinate kāma to spiritual goals, viewing excessive attachment as an obstacle to liberation (Radhakrishnan, 1923).

Sexual depiction sculptures, such as those at Khajuraho and Konark (9th–12th century CE), reflect the cultural acceptance of kāma within Hindu and Jain traditions, often symbolising fertility, divine union, or Tantric practices (White, 2000). These artworks are not tied to any darśana but illustrate the broader Indian worldview integrating kāma as a legitimate pursuit. In Tantric traditions, sexual imagery represents spiritual transcendence, distinct from philosophical concerns like ātman or causality (White, 2000).

The Concept of Karma

Karma (action and its consequences) is a central concept in most Indian philosophies, except Cārvāka, which rejects it outright (Sarvadarśanasaṅgraha, Mādhava, trans. Cowell & Gough, 1882). In āstika schools like Sāṃkhya, Yoga, Nyāya, Vaiśeṣika, Mīmāṃsā, and Vedānta, karma governs the cycle of birth and rebirth (saṃsāra), with actions producing moral consequences that shape future lives (Bhagavad Gītā 2.12–22, trans. Sargeant, 2009). Jainism and Buddhism also accept karma but reinterpret it: Jainism views karma as a material substance binding the soul (jīva), removable through asceticism (Jaini, 1979), while Buddhism sees it as a causal process driven by intention, not a creator God (Dhammapada, trans. Gethin, 1998).

Cārvāka’s rejection of karma stems from its materialist denial of an afterlife or non-empirical causality, arguing that only observable actions matter (Chattopadhyaya, 1959). The concept of karma underscores the ethical and metaphysical diversity of Indian philosophy, with most darśanas using it to explain existence and moral order, contrasting with Cārvāka’s focus on immediate experience.

Atheistic Foundations and Philosophical Rigor

The predominantly atheistic nature of Indian philosophy stems from its emphasis on rational inquiry over divine revelation (Dasgupta, 1922). Sāṃkhya and Vaiśeṣika developed causality and atomism without a deity; Cārvāka grounded its hedonism in sensory evidence; Jainism and Buddhism viewed the universe as eternal and uncreated. Even āstika schools like Mīmāṃsā prioritised ritual over a creator, while Nyāya and Vaiśeṣika’s later theistic elements were secondary (Radhakrishnan, 1923). The pramāṇas categorise these approaches:

- Direct Perception (pratyakṣa): Central to Cārvāka.

- Inference (anumāna): Key to Sāṃkhya, Nyāya, and Vaiśeṣika.

- Testimony (śabda): Essential for Mīmāṃsā and Vedānta.

- Combination: Buddhism and Jainism blend perception, inference, and insight.

Theism in Indian Philosophy: A Nuanced Perspective

Only Vedānta’s Dvaita and Viśiṣṭādvaita sub-schools align with Western theism, positing a personal God (Īśvara or Viṣṇu). Advaita Vedānta, however, views Brahman as impersonal, negating a creator (Brahmasūtras, trans. Thibaut, 1904). Indian theism, even in Vedānta, differs from Western monotheism, framing the creator as an aspect of ultimate reality (Sharma, 1960).

Thus, eight of the nine darśanas are atheistic by Western standards, focusing on rational, empirical, or meditative approaches.

Conclusion

Indian philosophy, with its nine darśanas, moves beyond theistic belief, prioritising rigorous inquiry. Dharma, broader than “religion,” underscores ethical and cosmic order (Rigveda, trans. Jamison & Brereton, 2014). Ātman, rejected by Buddhism and Cārvāka, and karma, rejected by Cārvāka alone, highlight metaphysical diversity. Kāma, as seen in the Kama Sutra and temple art, reflects cultural attitudes but is not a philosophical system (Doniger & Kakar, 2002). With only Vedānta’s theistic sub-schools resembling Western theism, Indian philosophy’s atheistic foundation and diverse pramāṇas make it a cornerstone of global discourse.

Further Reading

- Rigveda, trans. Stephanie W. Jamison and Joel P. Brereton. Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Upaniṣads, trans. Patrick Olivelle. Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Sāṃkhya Kārikā, trans. Gerald J. Larson. Motilal Banarsidass, 1969.

- Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali, trans. Edwin F. Bryant. North Point Press, 2009.

- Nyāya Sūtras, trans. Bimal Krishna Datta. Calcutta University Press, 1939.

- Vaiśeṣika Sūtras, trans. Nandalal Sinha. Sacred Books of the Hindus, 1911.

- Pūrva Mīmāṃsā Sūtras, trans. Ganganath Jha. Motilal Banarsidass, 1942.

- Brahmasūtras, trans. George Thibaut. Sacred Books of the East, 1904.

- Bhagavad Gītā, trans. Winthrop Sargeant. SUNY Press, 2009.

- Sarvadarśanasaṅgraha, Mādhava, trans. E.B. Cowell and A.E. Gough. Kegan Paul, 1882.

- Chattopadhyaya, Debiprasad. Lokāyata: A Study in Ancient Indian Materialism. People’s Publishing House, 1959.

- Dasgupta, Surendranath. A History of Indian Philosophy, Vol. 1–5. Cambridge University Press, 1922–1955.

- Doniger, Wendy, and Sudhir Kakar, trans. Kama Sutra. Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Flood, Gavin. An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Gethin, Rupert. The Foundations of Buddhism. Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Jaini, Padmanabh S. The Jaina Path of Purification. University of California Press, 1979.

- Matilal, Bimal Krishna. The Collected Essays of Bimal Krishna Matilal: Ethics and Epics. Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli. Indian Philosophy, Vol. 1–2. Oxford University Press, 1923.

- Sharma, Chandradhar. A Critical Survey of Indian Philosophy. Motilal Banarsidass, 1960.

- White, David Gordon. Tantra in Practice. Princeton University Press, 2000.

Leave a comment