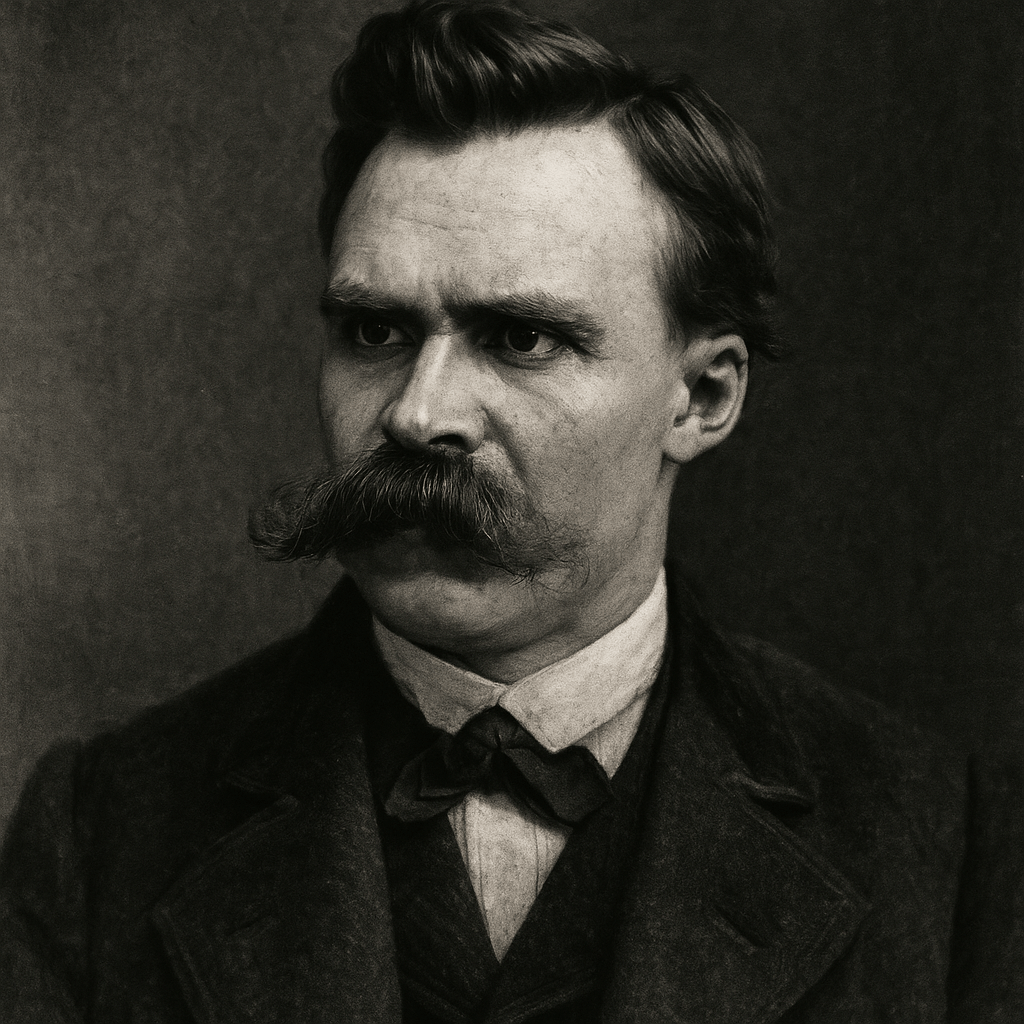

What if your instinct to help others is actually doing more harm than good? It’s a question most of us would rather avoid. Kindness is sacred — beyond scrutiny. But Friedrich Nietzsche, the 19th-century philosopher who famously declared “God is dead,” wasn’t one to tiptoe around sacred ideas. In On the Genealogy of Morality and Thus Spoke Zarathustra, he tears into the comfortable notion that helping others is always noble.

For Nietzsche, compassion that’s driven by pity or moral duty doesn’t just drain those we try to help. It saps vitality from us too. His challenge is as uncomfortable today as it was then. It forces us to rethink what “being good” actually means.

Imagine a mate who’s gutted after bombing a job interview. You jump in with reassuring words, maybe even offer to polish their CV. It feels like the decent thing to do. But Nietzsche would have you pause. Are you helping because you genuinely believe in their potential? Or because their distress makes you uneasy?

In On the Genealogy of Morality, he warns that pity is “the most sinister symptom of a society that has secretly turned against life” (Second Essay, Section 14). Pity, he argues, doesn’t just comfort — it spreads. Like a contagion, it teaches people to stay fragile, to lean on others rather than stand tall. By rushing to “fix” your mate’s pain, you might actually rob them of the chance to grow through struggle. Worse, you’re reinforcing a culture that celebrates weakness over resilience.

This idea links straight into Nietzsche’s concept of “slave morality.” It’s his term for how the powerless — historically the oppressed — turned their weakness into a kind of moral victory. Unable to strike back with strength, they created a value system that praised humility, self-sacrifice and pity, while branding ambition and power as evil (Genealogy, First Essay, Section 13).

Sound familiar? Think of the colleague who sighs about their workload, guilting you into picking up the slack. Or the influencer flooding your feed with posts about their latest charity work, fishing for likes more than real change. That’s slave morality in 2025 — helping (or begging for help) as a subtle manipulation, not as a bold act of creation. Nietzsche’s point stings: when we help because “it’s what good people do,” we’re often just following a script that punishes standing out and rewards staying small.

But Nietzsche isn’t saying we should never help. Far from it. He’s all for helping — as long as it flows from what he calls the “will to power,” that inner drive to create, to thrive, to overflow with life. In Thus Spoke Zarathustra, he writes, “All great love is above all pity: for it wants to—create what is loved!” (Part II, “On the Pitying”).

This is help that doesn’t coddle — it challenges. Picture a teacher who refuses to lower the bar for a struggling student, pushing them to master the material through grit. Or a mate who, instead of soothing your breakup pain, drags you to the gym to channel it into something stronger. That kind of help is like a river brimming over — giving because it’s full, not because it’s been guilt-tripped (Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Part I, “The Bestowing Virtue”). It builds, transforms, affirms life.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the workplace. Ever had a boss who “helps” by micromanaging every detail, rewriting your reports to “save” you from mistakes? It might look like care. Nietzsche would call it pity — and a subtle sabotage. It kills initiative, keeping you dependent instead of daring.

A true Nietzschean leader does the opposite. Think of someone like Emma Hayes, the Chelsea FC Women’s manager, known for pushing her players to their limits with tough love, not hand-holding. She doesn’t shield them from pressure. She trusts them to rise under it, forging a team that dominates. That’s help from strength, not weakness. In the office, it means setting high standards and believing in your team’s ability to meet them, not playing saviour.

Nietzsche’s critique hits hard because it challenges our deepest moral instincts. We’re taught that selflessness is the ultimate virtue. But he forces us to ask: Are we helping to truly lift someone up, or just to feel like a “good person”? Are we enabling fragility because it’s easier than watching someone struggle?

Look around. Parents who solve every maths problem for their kids aren’t helping — they’re stealing resilience. Social media crusaders who pile on to “defend” a cause often care more about looking moral than making a real difference. These are the fingerprints of slave morality: acts of “kindness” that serve the ego, not life. Nietzsche’s warning is stark. Helping from fear or guilt doesn’t just hold others back — it dims your own spark.

So how do you help in a way Nietzsche might actually respect? Pause before you act and ask yourself:

- Is this coming from my strength, or am I dodging discomfort?

- Will my help spark growth, or just soothe pain?

- Would I do this if no one was watching, or is it about looking “good”?

True help, for Nietzsche, transforms. It demands more, not less. It’s the difference between handing someone a crutch and teaching them to sprint.

Nietzsche doesn’t want you to stop helping. He wants you to stop weakening. Your kindness should build strength, not dependency. Next time you’re about to play the hero, ask: Am I creating something greater, or just propping up what’s broken? Be brutally honest.

The world needs more creators, fewer comforters. So, when’s the last time you helped someone and felt it truly lifted them? Or caught yourself helping just to ease your own awkwardness? Maybe you’ve seen a leader crush a team’s spirit with “kindness.” Share your story below — Nietzsche would relish the raw truth.

Leave a comment