Dialectics is a fundamental method of understanding progress and change, first identified as a mode of reasoning by ancient philosophers like Socrates and Plato, and later systematised by the German idealist philosopher G. W. F. Hegel.

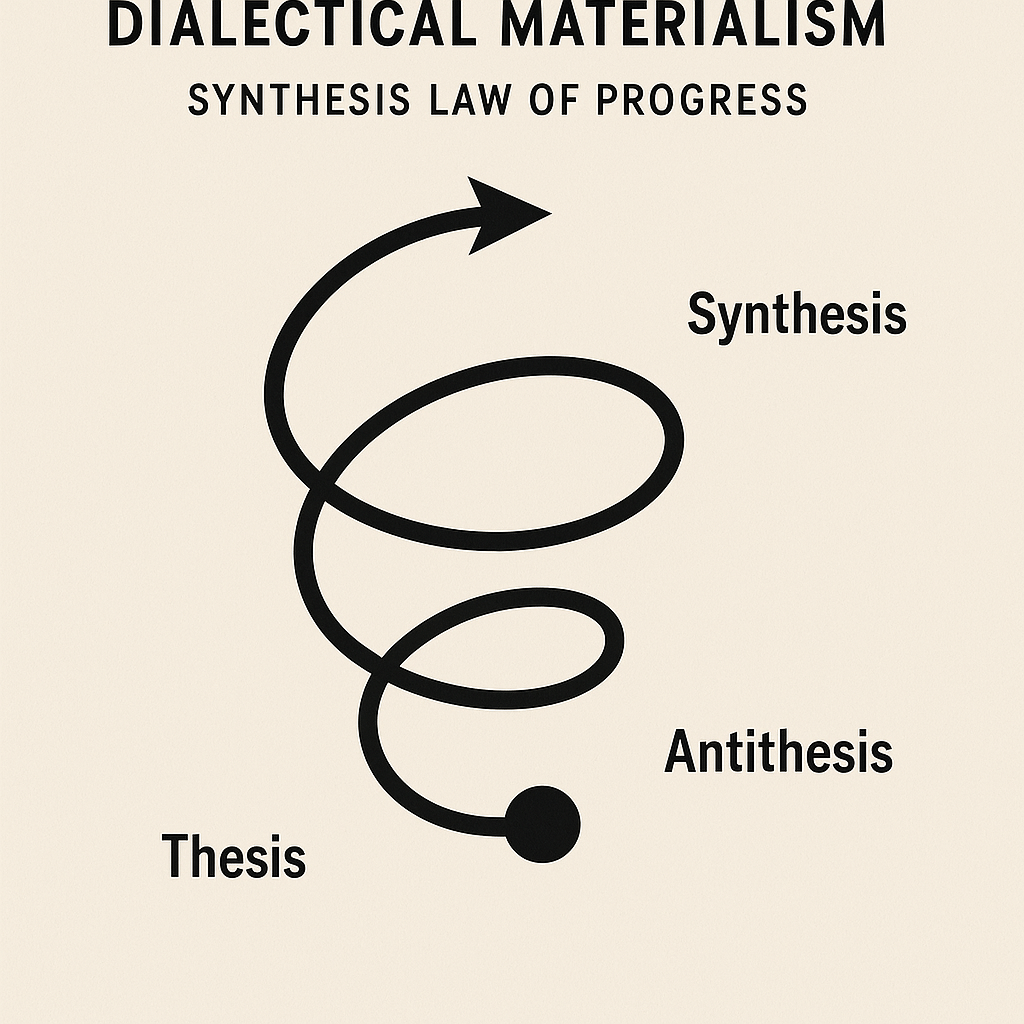

Hegel formulated dialectics as a dynamic process where a concept or state of affairs (a thesis) inevitably generates its opposite (an antithesis). The conflict between these two is resolved through a synthesis, which transcends and unites elements of both, creating a new, higher-stage thesis. This cycle then repeats, driving historical and intellectual evolution. However, Hegel saw this as a process of the unfolding of Geist or Spirit (a world mind or idea); his dialectic was primarily concerned with the progression of thought and consciousness.

Karl Marx, alongside his collaborator Frederick Engels, “stood Hegel on his feet.” They argued that Hegel’s dialectic was mystified and upside-down, concerned with the world of ideas rather than material reality. Marx inverted this framework, positing that the dialectic is not a journey of the Spirit but a law of nature and, crucially, of human history and economics. This materialist reinterpretation became the foundation of Dialectical Materialism.

At its core, dialectics posits that all things are composed of and defined by the unity and struggle of opposites. Contradictory forces—such as positive and negative, hot and cold, or in society, the exploiter and the exploited—are not just in conflict but are intrinsically linked. It is through their interaction, collaboration, and collision that development and progress occur.

Marx applied this natural principle to the class structure of capitalist society. He identified the primary opposing forces as the bourgeoisie (the capitalist class who own the means of production) and the proletariat (the working class who sell their labour). According to Marx, the inherent conflict, or class struggle, between these two is the engine of historical change under capitalism. This struggle would inevitably lead to the overthrow of the capitalist system and its replacement with socialism. The dialectical process would continue under socialism, eventually leading to a classless, stateless society: communism.

Frederick Engels later formalised the laws of dialectical materialism into three core principles:

- The Law of the Unity and Conflict of Opposites: Contradiction is inherent in all things and is the primary driver of change.

- The Law of the Passage of Quantitative Changes into Qualitative Changes: Incremental changes reach a tipping point, producing sudden transformation (water heating until it boils into steam).

- The Law of the Negation of the Negation: Development follows a spiral, where each stage negates the previous but preserves part of it, moving to a higher level rather than returning to the original.

Later revolutionaries took these laws from theory into practice. Vladimir Lenin analysed Russian society through a dialectical lens and argued that capitalism, in its imperialist stage, had sharpened contradictions to breaking point. He identified the central contradiction as that between imperialist powers seeking global markets and the exploited peoples and nations under their dominance. In Russia itself, Lenin judged that the contradiction between the autocratic state and the working masses could not be resolved through reform but only by revolution. He developed the concept of a vanguard party, a disciplined force capable of recognising these contradictions and leading the proletariat in the seizure of power. His interpretation was not without controversy, but it was dialectics applied as strategy: contradictions demanded decisive rupture.

Mao Zedong, writing in the very different conditions of a largely agrarian China, extended the dialectical method further. In his essay “On Contradiction”, Mao distinguished between principal and secondary contradictions. He argued that while many contradictions exist simultaneously, only one is decisive in any given historical moment. In China, he judged the principal contradiction to be between the peasantry and the landlord class, rather than between industrial workers and capitalists as in Europe. This insight allowed him to root revolution in the countryside and to place the peasantry at the heart of the struggle. Mao also distinguished between antagonistic contradictions (which require forceful resolution) and non-antagonistic ones (which can be handled through discussion and reform).

Both Lenin and Mao claimed to be faithful interpreters of Marx and Engels, yet their applications reveal the pliability of dialectics. Lenin redefined the dialectic of capitalism in terms of imperialism, while Mao recast it in terms of agrarian struggle and national liberation. Whether rightly or wrongly, each believed they were not merely theorising but living the law of contradiction, transforming it from philosophy into revolutionary practice.

The enduring lesson is that dialectics is never simply descriptive; it is prescriptive. It urges us to see contradictions not as accidents but as the very heartbeat of change. Hegel saw this in the drama of ideas, Marx in the struggles of class, Lenin in the fractures of imperialism, and Mao in the upheavals of peasant revolution. Each in their way sought to interpret, and act upon, the law. The question that remains is not whether contradictions exist—they are everywhere—but how we understand them, and what we choose to do with them.

Leave a comment